Two

Rebel Hats

By Fred Adolphus, May 28, 2014

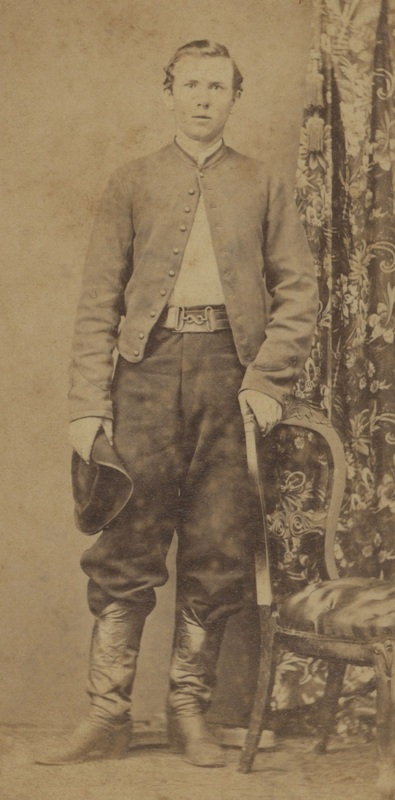

The slouch hat is one of the most enduring icons of the Confederate soldier, ranking alongside his kepi, bedroll, shell jacket and pants cuffs tucked into his socks. Indeed, the slouch hat came to be the quintessential American military campaign headgear by the end of the Civil War, meeting with both universal usage and approval during the Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War and World War One. It was superseded by the helmet once American troops got to France in 1917, and remained marginalized until the Vietnam War, when it made a huge come-back as the jungle hat. Since then, American soldiers have worn a version of the slouch hat in Southwest Asia in the form of the "boonie hat." No American soldier, however, has taken ownership of the slouch the way Johnny Reb did in the War for Southern Independence.

By Fred Adolphus, May 28, 2014

The slouch hat is one of the most enduring icons of the Confederate soldier, ranking alongside his kepi, bedroll, shell jacket and pants cuffs tucked into his socks. Indeed, the slouch hat came to be the quintessential American military campaign headgear by the end of the Civil War, meeting with both universal usage and approval during the Indian Wars, the Spanish-American War and World War One. It was superseded by the helmet once American troops got to France in 1917, and remained marginalized until the Vietnam War, when it made a huge come-back as the jungle hat. Since then, American soldiers have worn a version of the slouch hat in Southwest Asia in the form of the "boonie hat." No American soldier, however, has taken ownership of the slouch the way Johnny Reb did in the War for Southern Independence.

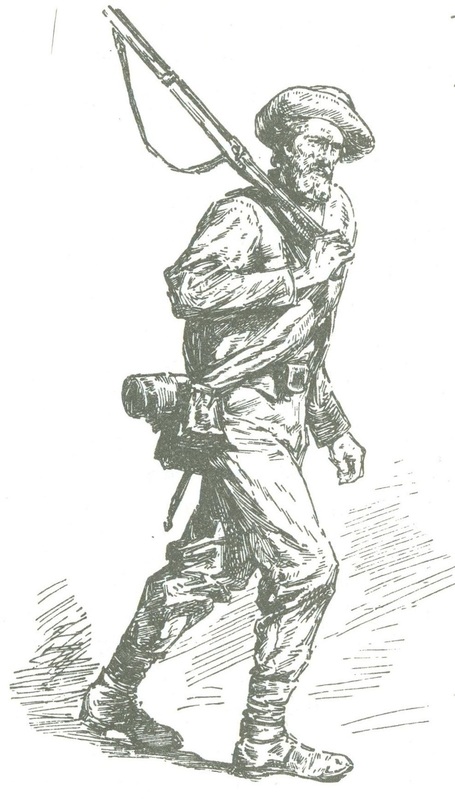

Image 1: Winslow Homer captured the essence of the Confederate slouch hat in his 1866 painting, "Prisoners from the Front." Both the drab white, turned up slouch, and the black, possibly imported hat are both present in this incredibly accurate rendering of Lee's soldiers during the Siege of Petersburg. Painting from the Metropolitan Museum of Art collection, New New York.

The

Confederate slouch hat was adopted for numerous reasons: it was well-liked,

practical and available (when caps were not).

Despite the regulation prescribing the French kepi-style cap for wear by

all soldiers and officers, many were not able to obtain the cap. They had to use the common citizen slouch

hat. Moreover, the slouch hat was found

to be more practical: it was comfortable and provided better protection against

the elements (sun, wind and rain). General Order Number 4, from the Texas State

Adjutant General's Office, dated June 10, 1861, reflects the overall sentiments

in favor of the slouch hat. The order

calls for each volunteer to supply himself with "one hat," among

other things, noting that the clothing need not be a uniform, but rather

"…of a type to be used for warmth and utility…" A public in the Clarksville, Texas

"Standard" newspaper offered similar

advice to volunteers of the 29th Texas Cavalry in August 1862. Therein, an "Old Soldier" remarked,

"The best military hat in use is the light-colored soft felt, the crown

being sufficiently high to allow space for air over the brain. -You can fasten it up as a continental in

fair weather, or turn it down when it is wet or very sunny."[1] It is not, therefore surprising that so many

volunteers took their wool hats with them to muster. This headgear was so comfortable that it was

never fully replaced by the military cap and was, in fact, retained by most

soldiers throughout the war, even as caps became readily available. The soft felt or wool hat predominated as the

Confederate army headgear. Captain John W. Greene, a Union officer escaping

from Camp Ford prison in East Texas, drives this point home with his comments

on the universality of the wool hat, stating, "As a disguise, we donned

the gray jacket and wool hat of the Confederate uniform, which had been

obtained through the assistance of negroes, and bidding our comrades farewell,

we passed out of the stockade..."[2]

The first Confederate hats were common citizen hats by and large, but as the war dragged on, the government began to produce, or procure army hats. The focus of this study is on the latter: the government issued hats. These were simple and cheap, made of felted wool, rather than higher-quality rabbit hair. For the most part, these two typical quartermaster hats consisted of the very cheap, low quality, Southern made, undyed drab hat, and the slightly higher quality black hat, frequently imported from Great Britain. These two types have come to define the rugged look of Johnny Reb, and this study tells their story.

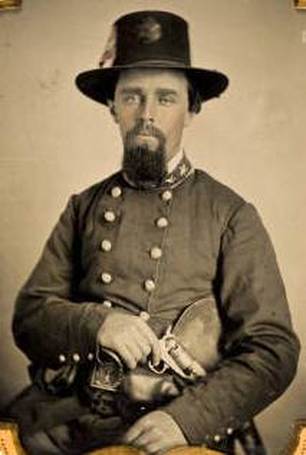

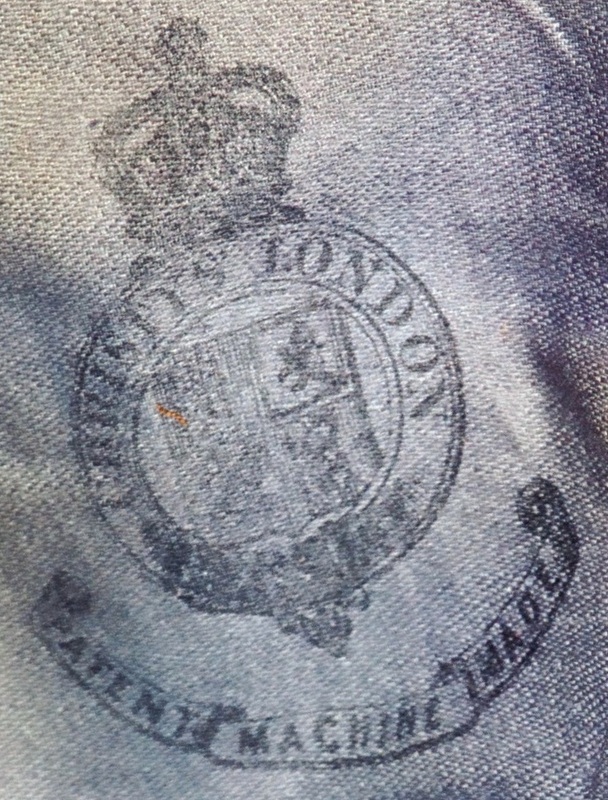

The ubiquitous and fashionable black hat is the first of the two typical hats to be studied. I have found the most evidence for imported, British-made hats being used in Texas and Virginia, but they were probably used throughout the Confederacy. The contracted black wool hat probably predated the government made drab hat, simply because it was quick and easy to let contracts for high quality hats, while it took some time to set up government hat factories, and these were not as proficient as the existing hat makers. During the first part of the war, quartermasters were content to let contractors supply hats, while they concentrated on making shoes, shirts, drawers, pants and jackets, and the easily fabricated cap. Likewise, contractors made relatively few caps, leaving this to the depots. The Confederacy imported hats until the end of the war, as Confederate Quartermaster General A.R. Lawton's guidance to foreign procurement agents in 1864 indicates, "A cheap and serviceable felt hat would be very acceptable to the Army."[3]

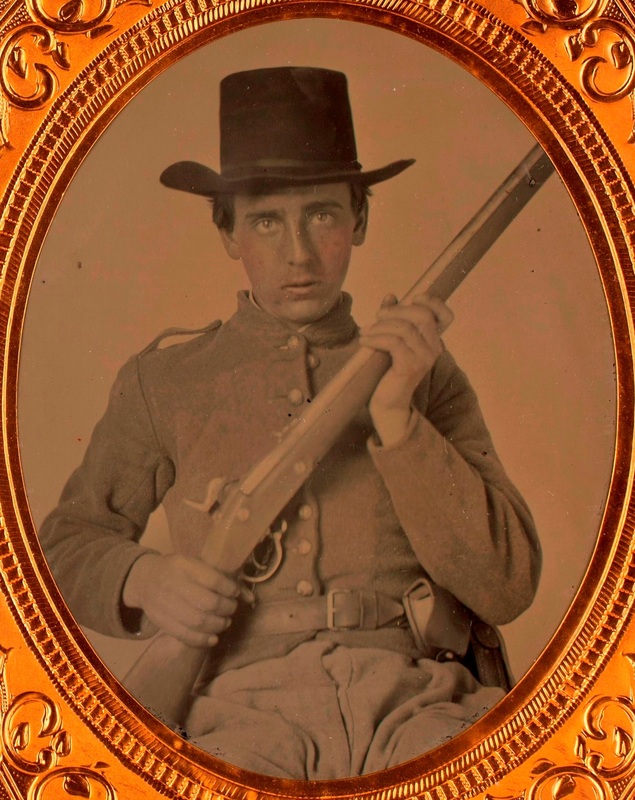

Some surviving clothing contracts from the Trans-Mississippi describe the black wool hat ordered by Confederate quartermasters throughout the war. Indeed, numerous photos, descriptions and surviving hats attest to its widespread usage everywhere in the South. Two agreements orchestrated by Confederate Quartermaster, Major Minter, include specifications for hats from Justin McCarthy, and Lippman & Koppel. Justin McCarthy's agreement called for, "...Five Thousand good black Wool Hats the quality and style of which to be of the pattern (as near as practicable) known as the U.S. Cavalry Hat." The price per hat was set at $5.00 each. Delivery was to be made before May 1, 1863 at San Antonio.[4] Lippmann & Koppel's agreement called for the import of 6,000 hats at $6.00 each, delivering them before April 6, 1863. The specifications called for, "...Five hundred dozen, more or less, of good black Wool Hats, of the quality and style of a hat exhibited to Mr Koppel, partner of the said firm Lippman & Koppel, and Known as the "Army Hat"..."[5]

Notably, both agreements called for the same type of hat that the U.S. Army issued to its troops, that being the pattern 1858 army hat (without any trimmings, however). The Union army hat and the earlier pattern cavalry hat both had the same basic shape and outward appearance. Both were black felt with high, slightly tapering crowns. The cavalry hat had a 3" wide brim and a 6 1/2" high crown, while the army hat had a 3 1/4" wide brim and a 6 1/4" crown.[6] This reflects the prevailing popular style of hat, as well as the Quarter Master Department's affection for the "Old Army" style hat.

By the spring of 1863, imported hats were arriving in Texas. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle, a visiting British officer, alluded to this on April 6, 1863, remarking, "At noon I crossed to Brownsville and visited Captain Lynch, a quartermaster, who broke open a great box, and presented me with a Confederate felt hat to travel in." F.J. Lynch provided Fremantle with the hat that he would wear throughout his travels in Dixie.[7] Fremantle also commented, at the same time and place, that troopers of Duff's 33rd Texas Cavalry, "...all wore the high black felt hat...ornamented with the 'lone star of Texas'."[8] This gives the impression that the imported hats, of the style Minter ordered, were being issued to Texas soldiers already, and that Fremantle's Confederate felt hat was one of the same. Further evidence suggests the issue of British-made, imported hats in South Texas during 1863, as well. The 4th Arizona Cavalry drew hats at San Antonio in May costing $6.00 each, the exact price of the Lippmann & Koppel hats. In June, the 3rd Texas Infantry, stationed at Brownsville, drew some "Uniform Hats" at $5.00 each. Both the price and the description indicate that they were McCarthy hats.[9]

A shipment of 5,460 "Black Wool Hats" arrived in Brownsville, Texas in the fall of 1863 on the blockade runner Sir William Peel. The Peel invoice offers more evidence for British-made hats arriving in the Trans-Mississippi. It also correlates with statements made by the Chief of the Texas Clothing, Captain E.C. Wharton in May and July of 1863. Wharton requested that black wool hats be given the troops in place of caps, and he compiled clothing requirements for hats, rather than caps, as well. Not having the facilities to make hats, he stated that he had to rely that year on imports for this article.[10]

Corresponding to the written records, there are a few surviving, bona fide imported British-made hats, and several probable imports, as well as numerous photos of likely imported hats. The problem is that it is difficult to distinguish between an imported enlisted hat and a similar one made in the South. Therefore, the study is not an exact science, but, enough evidence proves that imported black hats were common, so at least some the hats selected as examples are likely to be British imports.

Before imported hats were available, local contractors offered "felt" hats to quartermasters. In the summer of 1862 at Matagorda, the 26th Texas Cavalry some of these hats, priced at $2.25, $2.50 and $3.00 each, but without mentioning their color.[11] In April 1862, the 3rd Texas Infantry received some "hats, citizen" for $2.35 each, and in the summer of 1863, they received some "black hats" at $2.25 each. Also during the summer of 1863, the 36th Texas Cavalry drew "Hats, Cavalry" at $1.25 each. The later may have been part of the "Old Army" stock captured in San Antonio in February 1861.[12]

Several private hat makers operated in the East Texas, and provided locally made contract hats for the Confederacy. These included the Southern Hattery in Marshall, the C.S.A. Hat Factory in Gilmer and some smaller contractors in and around Harrison County. The C.S.A. Hat Factory advertised that it made hats for Southern Troops, while the Southern Hattery manufactured hats "...exclusively for Texas Confederates".[13] Two agreements made at Jefferson, Texas provide some details. One agreement made on 19 January 1863, with I. & L. Benz of Harrison County was for the delivery of 200 wool hats, at $3.00 each, by 10 March 1863, with another 500 more to be delivered later. Another agreement with a Mr. R. Knight was for the delivery of 1,000 wool hats per month at $3.50 each, to commence 10 May 1863. [14] Indeed, during January 1864, members of the 11th Texas Infantry drew "Wool Hats" for $3.00 apiece, possibly some made by I. & L. Benz.[15]

The first Confederate hats were common citizen hats by and large, but as the war dragged on, the government began to produce, or procure army hats. The focus of this study is on the latter: the government issued hats. These were simple and cheap, made of felted wool, rather than higher-quality rabbit hair. For the most part, these two typical quartermaster hats consisted of the very cheap, low quality, Southern made, undyed drab hat, and the slightly higher quality black hat, frequently imported from Great Britain. These two types have come to define the rugged look of Johnny Reb, and this study tells their story.

The ubiquitous and fashionable black hat is the first of the two typical hats to be studied. I have found the most evidence for imported, British-made hats being used in Texas and Virginia, but they were probably used throughout the Confederacy. The contracted black wool hat probably predated the government made drab hat, simply because it was quick and easy to let contracts for high quality hats, while it took some time to set up government hat factories, and these were not as proficient as the existing hat makers. During the first part of the war, quartermasters were content to let contractors supply hats, while they concentrated on making shoes, shirts, drawers, pants and jackets, and the easily fabricated cap. Likewise, contractors made relatively few caps, leaving this to the depots. The Confederacy imported hats until the end of the war, as Confederate Quartermaster General A.R. Lawton's guidance to foreign procurement agents in 1864 indicates, "A cheap and serviceable felt hat would be very acceptable to the Army."[3]

Some surviving clothing contracts from the Trans-Mississippi describe the black wool hat ordered by Confederate quartermasters throughout the war. Indeed, numerous photos, descriptions and surviving hats attest to its widespread usage everywhere in the South. Two agreements orchestrated by Confederate Quartermaster, Major Minter, include specifications for hats from Justin McCarthy, and Lippman & Koppel. Justin McCarthy's agreement called for, "...Five Thousand good black Wool Hats the quality and style of which to be of the pattern (as near as practicable) known as the U.S. Cavalry Hat." The price per hat was set at $5.00 each. Delivery was to be made before May 1, 1863 at San Antonio.[4] Lippmann & Koppel's agreement called for the import of 6,000 hats at $6.00 each, delivering them before April 6, 1863. The specifications called for, "...Five hundred dozen, more or less, of good black Wool Hats, of the quality and style of a hat exhibited to Mr Koppel, partner of the said firm Lippman & Koppel, and Known as the "Army Hat"..."[5]

Notably, both agreements called for the same type of hat that the U.S. Army issued to its troops, that being the pattern 1858 army hat (without any trimmings, however). The Union army hat and the earlier pattern cavalry hat both had the same basic shape and outward appearance. Both were black felt with high, slightly tapering crowns. The cavalry hat had a 3" wide brim and a 6 1/2" high crown, while the army hat had a 3 1/4" wide brim and a 6 1/4" crown.[6] This reflects the prevailing popular style of hat, as well as the Quarter Master Department's affection for the "Old Army" style hat.

By the spring of 1863, imported hats were arriving in Texas. Lieutenant Colonel Arthur Fremantle, a visiting British officer, alluded to this on April 6, 1863, remarking, "At noon I crossed to Brownsville and visited Captain Lynch, a quartermaster, who broke open a great box, and presented me with a Confederate felt hat to travel in." F.J. Lynch provided Fremantle with the hat that he would wear throughout his travels in Dixie.[7] Fremantle also commented, at the same time and place, that troopers of Duff's 33rd Texas Cavalry, "...all wore the high black felt hat...ornamented with the 'lone star of Texas'."[8] This gives the impression that the imported hats, of the style Minter ordered, were being issued to Texas soldiers already, and that Fremantle's Confederate felt hat was one of the same. Further evidence suggests the issue of British-made, imported hats in South Texas during 1863, as well. The 4th Arizona Cavalry drew hats at San Antonio in May costing $6.00 each, the exact price of the Lippmann & Koppel hats. In June, the 3rd Texas Infantry, stationed at Brownsville, drew some "Uniform Hats" at $5.00 each. Both the price and the description indicate that they were McCarthy hats.[9]

A shipment of 5,460 "Black Wool Hats" arrived in Brownsville, Texas in the fall of 1863 on the blockade runner Sir William Peel. The Peel invoice offers more evidence for British-made hats arriving in the Trans-Mississippi. It also correlates with statements made by the Chief of the Texas Clothing, Captain E.C. Wharton in May and July of 1863. Wharton requested that black wool hats be given the troops in place of caps, and he compiled clothing requirements for hats, rather than caps, as well. Not having the facilities to make hats, he stated that he had to rely that year on imports for this article.[10]

Corresponding to the written records, there are a few surviving, bona fide imported British-made hats, and several probable imports, as well as numerous photos of likely imported hats. The problem is that it is difficult to distinguish between an imported enlisted hat and a similar one made in the South. Therefore, the study is not an exact science, but, enough evidence proves that imported black hats were common, so at least some the hats selected as examples are likely to be British imports.

Before imported hats were available, local contractors offered "felt" hats to quartermasters. In the summer of 1862 at Matagorda, the 26th Texas Cavalry some of these hats, priced at $2.25, $2.50 and $3.00 each, but without mentioning their color.[11] In April 1862, the 3rd Texas Infantry received some "hats, citizen" for $2.35 each, and in the summer of 1863, they received some "black hats" at $2.25 each. Also during the summer of 1863, the 36th Texas Cavalry drew "Hats, Cavalry" at $1.25 each. The later may have been part of the "Old Army" stock captured in San Antonio in February 1861.[12]

Several private hat makers operated in the East Texas, and provided locally made contract hats for the Confederacy. These included the Southern Hattery in Marshall, the C.S.A. Hat Factory in Gilmer and some smaller contractors in and around Harrison County. The C.S.A. Hat Factory advertised that it made hats for Southern Troops, while the Southern Hattery manufactured hats "...exclusively for Texas Confederates".[13] Two agreements made at Jefferson, Texas provide some details. One agreement made on 19 January 1863, with I. & L. Benz of Harrison County was for the delivery of 200 wool hats, at $3.00 each, by 10 March 1863, with another 500 more to be delivered later. Another agreement with a Mr. R. Knight was for the delivery of 1,000 wool hats per month at $3.50 each, to commence 10 May 1863. [14] Indeed, during January 1864, members of the 11th Texas Infantry drew "Wool Hats" for $3.00 apiece, possibly some made by I. & L. Benz.[15]

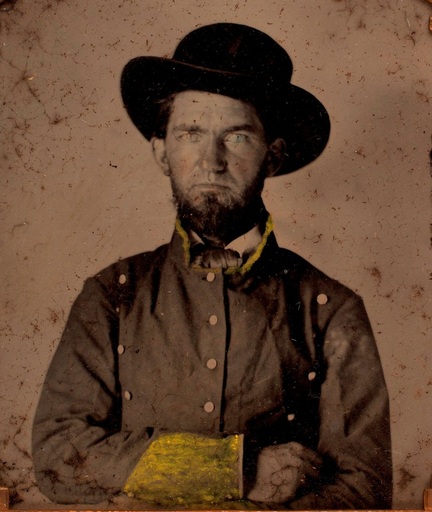

We

can now turn our attention to the Southern-made, undyed, drab wool hat. The use of this type of hat was universal

throughout the South, as numerous surviving examples, contemporary descriptions

and photos attest. While my own research

focuses on the Trans-Mississippi Department, the evidence found there is

applicable to the rest of the Confederacy.

Captain E.C. Wharton's records are a useful starting point, since

Wharton was the Chief of the Clothing Bureau in Texas until February 1864.

Wharton's first remarks on the topic are from May 16, 1863, when he specifically stated that wool hats should be issued in place of caps. Again in July, he mentioned that black wool hats, instead of caps, should be given to the troops. Finally, he established his own hat factory late in 1863, in order to fabricate "a plain but serviceable wool hat ‑ of which the Troops stand much in need."[16] When justifying the need for a hat factory in Texas, Wharton said it was difficult to procure either caps or hats through contracts, due to their "exorbitant" prices ($4.00 per hat). He had a pressing need for 10,000 hats that November, and asserted a government factory could make good wool hats in large numbers at a rapid rate for not over $3.00 each.[17]

Wharton's first remarks on the topic are from May 16, 1863, when he specifically stated that wool hats should be issued in place of caps. Again in July, he mentioned that black wool hats, instead of caps, should be given to the troops. Finally, he established his own hat factory late in 1863, in order to fabricate "a plain but serviceable wool hat ‑ of which the Troops stand much in need."[16] When justifying the need for a hat factory in Texas, Wharton said it was difficult to procure either caps or hats through contracts, due to their "exorbitant" prices ($4.00 per hat). He had a pressing need for 10,000 hats that November, and asserted a government factory could make good wool hats in large numbers at a rapid rate for not over $3.00 each.[17]

Production on

Wharton's wool hat did not begin until early 1864. Until then he procured black wool hats

through the blockade, which have been described under contracted uniforms.[18] Wharton, however, did not establish the first

government hat factory in the Trans-Mississippi. Captain N.A. Birge operated the first factory

at the Shreveport Depot in early 1863.

He transferred 91 of his wool hats in the first quarter, and 542 in the second

quarter of that year, and the depot was still transferring wool hats in 1865.[19]

Captain Wharton even commented about

this successful hat factory in November 1863, opining that it was too far away

to supply his clothing bureau.[20]

Captain Wharton's

detailed hatter, Private Aaron T. Fuller of the 26th Texas Cavalry, began

construction on the hat factory on about December 4, 1863, and fabricated hats

there for the rest of the war. The

factory's first location is unclear: either San Antonio or Washington

County. Early in 1864, however, Major

John H. Kampmann assumed management under the name "Government Hat Factory." Kampmann had the factory in full production

by April, which enabled him to send hats to Houston for general issue. In May, Kampmann moved the operation to La

Grange, Fayette County, where it operated until the end of the war.[21]

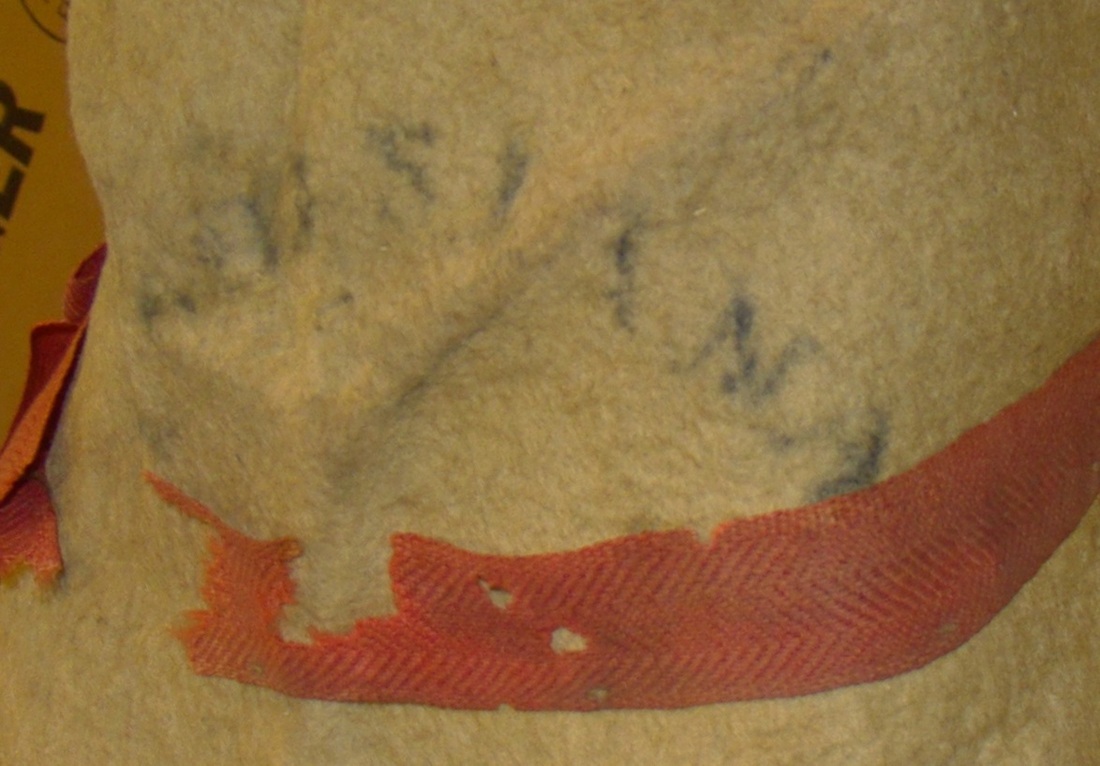

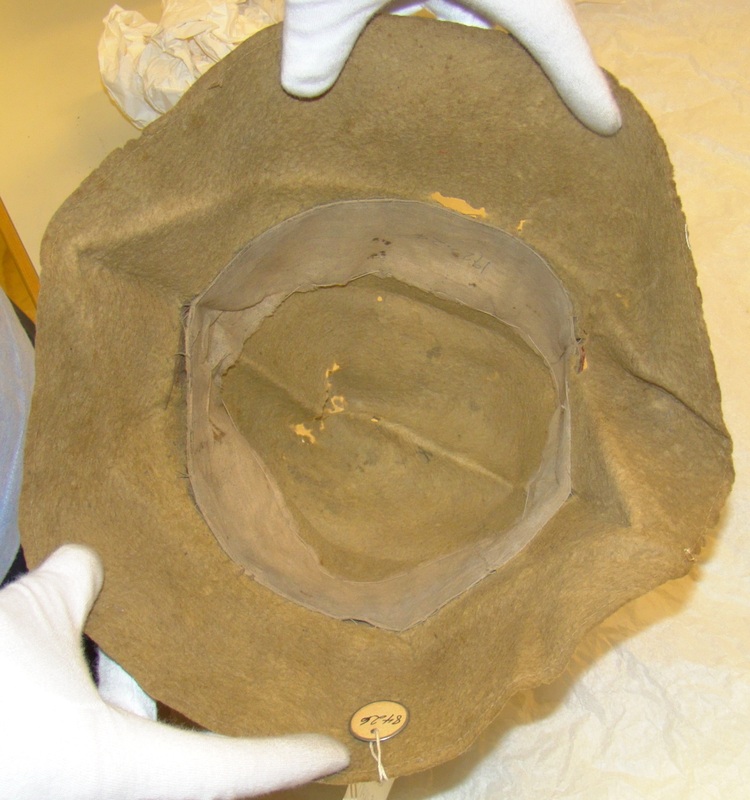

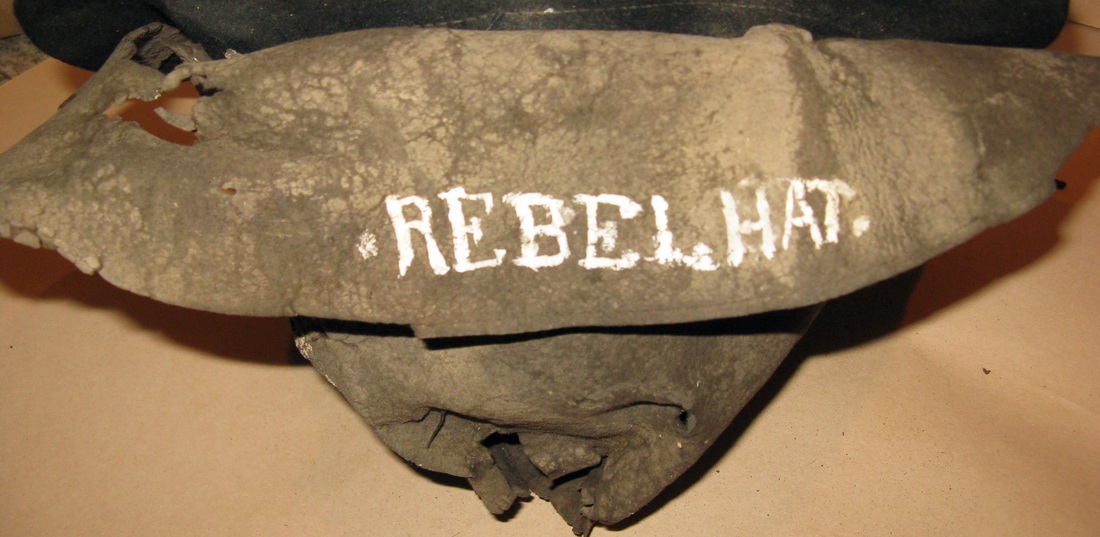

Image 64: Collector Steve Osman acquired this drab hat from a "time capsule" full of Civil War memorabilia that had been sealed in 1888 and opened in 1972. The “Rebel Hat” had been folded to about the size of a dollar bill and nailed to the back board. The authorities were going to discard it, but Steve Osman took it, and over time, carefully unfolded it. According to the hat's provenance, it was salvaged from the Gettysburg battlefield. The first owner marked the bottom of the brim, "REBEL HAT." Artifact courtesy of the Steve Osman collection.

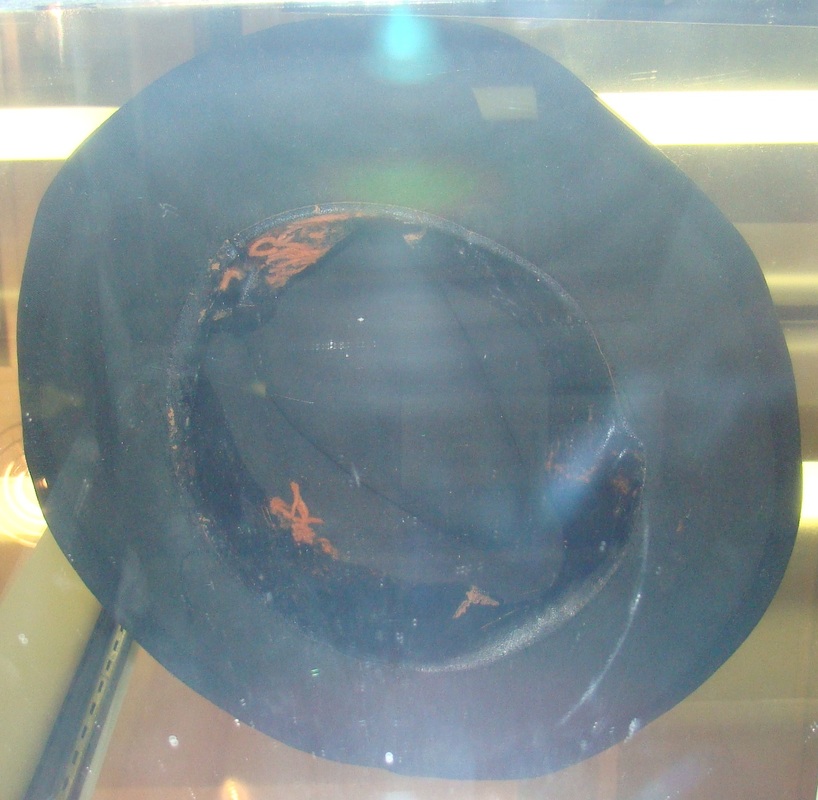

Regrettably, neither

the Shreveport nor the Texas factory mentioned the color of their hats or any

other specifications. A hat picked up on

the Fort Smith, Arkansas battlefield may be a product of one of these

operations. Furthermore, Lieutenant G.W.

Grayson, 2nd Creek Regiment, described one of these Confederate-made hats in the following passage: “Our

government had issued to our men certain wool hats which appeared to be

manufactured of the plain sheep’s wool without any coloring, while the hatter

seemed not to have seriously concerned himself about the symmetry and poise of

any individual hat. They were all

apparently on one block and driven together in long stacks, and when one came

near a stack of them he could distinctly discern the odor of the raw

material. It smelled very like getting

inside of a pen where a drove of sheep is confined. Now these hats, while not comely of shape and

general appearance, had the further disadvantage of losing after a short

service even the little shape and semblance of figure that had been given them

by the manufacturers. The entire brim

would invariably flop down, leaving little other signs of its former self than

a dirty string, while the crown, without any apparent provocation, would push

sharply up in the center, converting the whole into the exact figure of a

cone. These hats being a dull whitish

color were very susceptible to the

effects of dust and dirt, and naturally had a dingy appearance at best, which

became execrable after a month’s wear.

One such hat had well-nigh served its time and collected its full share

of dust and discolorations was owned and worn by McAnally.”[22] Grayson's description is not very

complimentary, but it definitely captures the full essence of the drab

Confederate enlisted hat!

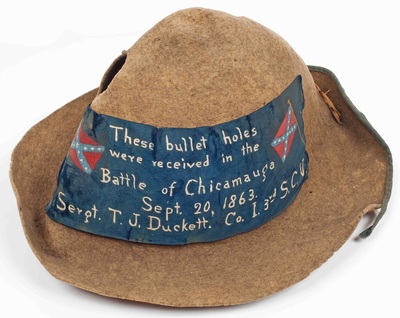

Image 67: A Confederate-made, drab hat recovered from the Fort Smith battlefield matches Grayson's description. Chaplain Ozem Gardner, 13th Kansas Infantry, took this hat and a sword from the body of a fallen Confederate soldier as souvenirs about September 1, 1863. The high point on this hat, and the floppy brim are symptoms of a poorly blocked hat. The hat's natural state is its first stage of blocking: the cone. As its shape deteriorates, the top of the crown pushes upward and the brim flops downward. It relaxes, so to speak, returning to the cone form. This hat is an example of the reverting process. Artifact and image courtesy of the Kansas Museum of History.

Putting aside the very prolific,

privately acquired hats that Southerners wore, the quartermaster essentially

issued two basic types: the Southern-made drab hat, and the imported British

black hat. Two Rebel hats that embedded

themselves in the imagination and lore of the Southern Confederacy as the

quintessential slouch hat. Long may it

endure!

The

author extends his gratitude to all of the institutions and private individuals

who made the images in this article available (as credited in the

captions). Readers are reminded that the

images herein are the property of Adolphus Confederate Uniforms, except where

noted as being in the public domain or the Library of Congress. Even if an artifact or image is

credited to a public institution, the image itself is the property of this

website, having been made by, purchased by or given usage of to the

author. Please do not reproduce these

images without the obtaining the author's consent.

Bibliography

[1]. Grady, John C. and Felmly, Bradford K., Suffering to Silence, 29th Texas Cavalry, CSA Regimental History, Nortex Press, Quanah, Texas, 1975, p. 12.

[2]. Greene, John W., An Incident of the Civil War, Camp Ford Prison and How I Escaped, Barkdull Printing House, Toledo, Ohio, 1893, p. 42.

[3] Official Records, War of the Rebellion, Series 4, Volume 3, page 674, Letter A.R. Lawton, QM General to Major J.B. Ferguson, QM, Richmond, Virginia, September 21, 1864.

[4] NARA, Record Group 109, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Microfilm 346, between Major Minter, quartermaster and McCarthy, November 5, 1862, for hats (hereafter, Confederate Contracts).

[5] Confederate Contracts, between Major Minter, quartermaster and Lippman & Koppel, October 6, 1862, for hats.

[6] Howell, Edgar M., United States Army Headgear, 1855-1902: Catalog of United States Army Uniforms in the Collections of the Smithsonian Institution, II, Smithsonian Institution Press, City of Washington, 1975, pp. 3-6.

[7] Lord, Walter; The Fremantle Diary: Being the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel James Lyon Arthur Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on his Three Months in the Southern States, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1954, pp. 7, 9 & 12 (hereafter, Fremantle).

[8] Fremantle, pp. 7 & 9, 2 Apr 63.

[9] NARA, Confederate Record Group 109, Compiled Service Records for Texas, M323, Rolls 273-280, 3rd Texas Infantry Regiment; and, Arizona, M318, 4th Regiment, Arizona Brigade, (hereafter, CSRs).

[10] Captain Edward C. Wharton, Chief Quartermaster, District of Texas, records 1862-1864, NARA, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Reports, M935, Reel 8, 89-J.41 through 158-J.41 (hereafter, Wharton), this reference 95-J.41.

[11] CSRs, Texas, Rolls 131-136, 26th Texas Cavalry Regiment.

[12] Texas State Archives, Confederate Quarter Master and Commissary Records, Record Group 401, Box 839, Folders 1 and 6, inventory of Old Army stock seized by Texas State forces in San Antonio, February 1861: included 4,857 Hardee hats.

[13] Bill Winsor, Texas in the Confederacy: Military Installations, Economy and People, Hill Junior College Press, Hillsboro, Texas, 1978, pp. 55-56

[14] Texas State Archives, Confederate Quarter Master and Commissary Records, Record Group 401, Box 851, Folder 20, contracts made by Captain Asa W. Wright, Post Quarter Master at Jefferson, Texas.

[15] CSRs, Texas, Rolls 344-355, 11th Texas Infantry Regiment.

[16] Wharton, this reference 89-J.41, pp. 71-72; 112-J.41; 113-J.41; and, 141-J.41.

[17] CSRs, Texas, Roll 132, 26th Texas Cavalry Regiment, records of Private Aaron T. Fuller.

[18] Wharton, 92-J.41 and 95-J.41.

[19] Captain N. A. Birge, Quartermaster Officer, Department of the Trans-Mississippi, University of Texas, Center for American History, General Papers of the Confederacy, Birge, Box 2C487, Folders 10, Birge expended 158 pounds of wool in making hats at his Shreveport Depot during the second quarter of 1863.

[20] CSRs, Texas, Roll 132, 26th Texas Cavalry Regiment, records of Private Aaron T. Fuller.

[21] CSRs, Texas, Rolls 273-280, 3rd Texas Infantry Regiment.

[22] A Creek Warrior for the Confederacy; The Autobiography of Chief G.W. Grayson, edited by W. David Baird, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London, 1988, page 97.

Bibliography

[1]. Grady, John C. and Felmly, Bradford K., Suffering to Silence, 29th Texas Cavalry, CSA Regimental History, Nortex Press, Quanah, Texas, 1975, p. 12.

[2]. Greene, John W., An Incident of the Civil War, Camp Ford Prison and How I Escaped, Barkdull Printing House, Toledo, Ohio, 1893, p. 42.

[3] Official Records, War of the Rebellion, Series 4, Volume 3, page 674, Letter A.R. Lawton, QM General to Major J.B. Ferguson, QM, Richmond, Virginia, September 21, 1864.

[4] NARA, Record Group 109, Confederate Papers Relating to Citizens or Business Firms, Microfilm 346, between Major Minter, quartermaster and McCarthy, November 5, 1862, for hats (hereafter, Confederate Contracts).

[5] Confederate Contracts, between Major Minter, quartermaster and Lippman & Koppel, October 6, 1862, for hats.

[6] Howell, Edgar M., United States Army Headgear, 1855-1902: Catalog of United States Army Uniforms in the Collections of the Smithsonian Institution, II, Smithsonian Institution Press, City of Washington, 1975, pp. 3-6.

[7] Lord, Walter; The Fremantle Diary: Being the Journal of Lieutenant Colonel James Lyon Arthur Fremantle, Coldstream Guards, on his Three Months in the Southern States, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, 1954, pp. 7, 9 & 12 (hereafter, Fremantle).

[8] Fremantle, pp. 7 & 9, 2 Apr 63.

[9] NARA, Confederate Record Group 109, Compiled Service Records for Texas, M323, Rolls 273-280, 3rd Texas Infantry Regiment; and, Arizona, M318, 4th Regiment, Arizona Brigade, (hereafter, CSRs).

[10] Captain Edward C. Wharton, Chief Quartermaster, District of Texas, records 1862-1864, NARA, Record Group 109, Confederate Inspection Reports, M935, Reel 8, 89-J.41 through 158-J.41 (hereafter, Wharton), this reference 95-J.41.

[11] CSRs, Texas, Rolls 131-136, 26th Texas Cavalry Regiment.

[12] Texas State Archives, Confederate Quarter Master and Commissary Records, Record Group 401, Box 839, Folders 1 and 6, inventory of Old Army stock seized by Texas State forces in San Antonio, February 1861: included 4,857 Hardee hats.

[13] Bill Winsor, Texas in the Confederacy: Military Installations, Economy and People, Hill Junior College Press, Hillsboro, Texas, 1978, pp. 55-56

[14] Texas State Archives, Confederate Quarter Master and Commissary Records, Record Group 401, Box 851, Folder 20, contracts made by Captain Asa W. Wright, Post Quarter Master at Jefferson, Texas.

[15] CSRs, Texas, Rolls 344-355, 11th Texas Infantry Regiment.

[16] Wharton, this reference 89-J.41, pp. 71-72; 112-J.41; 113-J.41; and, 141-J.41.

[17] CSRs, Texas, Roll 132, 26th Texas Cavalry Regiment, records of Private Aaron T. Fuller.

[18] Wharton, 92-J.41 and 95-J.41.

[19] Captain N. A. Birge, Quartermaster Officer, Department of the Trans-Mississippi, University of Texas, Center for American History, General Papers of the Confederacy, Birge, Box 2C487, Folders 10, Birge expended 158 pounds of wool in making hats at his Shreveport Depot during the second quarter of 1863.

[20] CSRs, Texas, Roll 132, 26th Texas Cavalry Regiment, records of Private Aaron T. Fuller.

[21] CSRs, Texas, Rolls 273-280, 3rd Texas Infantry Regiment.

[22] A Creek Warrior for the Confederacy; The Autobiography of Chief G.W. Grayson, edited by W. David Baird, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman and London, 1988, page 97.